2024:1

Learning is more than mathematical equations.

— First of a four-part series —

Decades after identifying the need for interpersonal or “affective” skills in the workplace, higher education still fails to deliver. The focus has remained on cognitive skills and even solely on quantitative subjects.

Well over a decade ago, studies identified a series of studies on 21st-century skills for the modern workplace, including a focus on the 4 Cs of communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. Essentially, these are key interpersonal or affective skills.

Despite the clear case for affective skills--meaning how we deal with things emotionally, such as feelings, values, appreciation, enthusiasms, motivations, and attitudes--we continue to ignore the clear need. We are often confronted with simplistic notions that teaching and learning STEM subjects will solve all of society’s problems. The recent hype around generative AI such as Chat GPT would have one believe that the only skill needed is data analytics.

Mastering cognitive skills does not guarantee that smart people can work together. In fact, history is littered with brilliant personalities who were unable to reach their full potential because of a lack of the 4 Cs.

The barrier to success as we work in complex organizations and seek to solve complex problems is often that smart people cannot work together effectively. Simply put, it is an issue of the lack of learned affective skills rather than knowledge and mastery of concepts and theories.

A theme heard at virtually every business or academic conference is around how to deal with constant and evolving change. The key skills of collaboration in problem-solving and change management are largely in an affective domain not some new theory or concept lending itself to cognitive skill building.

Doing better as educators will require that we come to grips with teaching and learning in both the cognitive and affective domains.

This series will address this area in four installments.

Clarifying the distinction between cognitive and affective skills and providing an overview of key 21st-century skills in the context of affective intelligence.

Flipping the script on the idea of competencies from KSA (usually knowledge, skills, and abilities) to ASK (attention, skills, and knowledge).

Examining the assessment challenges for affective skills using the example of collaborative problem-solving.

Describing a real-world example of how behavioral change in one of the most difficult affective areas of personal health—nutrition and weight loss—can actually be done at a distance using online and remote technologies.

Cognitive vs. affective learning

A default assumption when considering learning and education is that knowledge is key. The idea's foundation is that there are data, facts, elements, or concepts out there that need to be learned to be effective as humans. One could perhaps trace this notion to the ideas of enlightenment such as René Descartes's first principle of his philosophy, "I think, therefore I am" (Latin—cogito, ergo sum; or as he put it first in 1637—je pense, donc je suis).

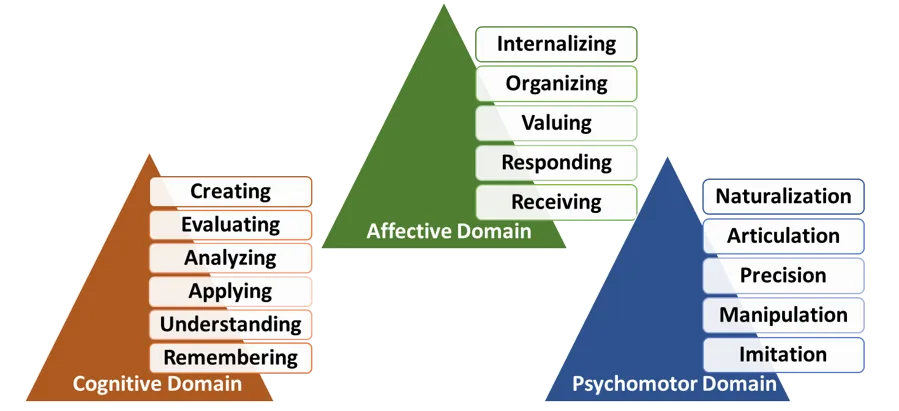

As education thought and theory evolved, notions of different types of knowledge or intelligence emerged. Approaches to measuring levels of knowledge and skill saw refinement as well. In 1956, Bernard Bloom published a taxonomy of cognitive learning. That was followed in 1965 by an affective taxonomy with David Krathwohl, one of Bloom’s co-authors, as the main author. These two taxonomies were followed by a third, the psychomotor domain, in 1972. The three taxonomies—with the cognitive domain updated in 2001—are foundational to educational program design and outcomes evaluation.

The three taxonomies or domains taken together provide a holistic view.

The distinctions inherent in the domains are important. The cognitive domain comes with a scientific view that there is knowledge “out there,” and it should somehow be captured, assimilated, and mastered. The affective domain is instead rooted in the level of skillfulness of one’s behavior in personal, interpersonal, and group settings. The psychomotor domain looks at the skillfulness of our ability to move and accomplish physical tasks of increasing complexity.

Despite the existence of three distinct learning domains, educational practice is often stuck in the cognitive domain. The myopic focus on programs and skills such as STEM and data analytics illustrates the lack of a broader focus. Curriculum designers are taught to ignore affective skills because they are just too difficult to fit into the model of testing and assessment common in education.

Enter the 21st-century skills

The multiple turn-of-the-century projects sought to define the knowledge and skills needed in economies driven by rapid technological evolution and interconnectivity. The inventory of skills includes critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, communication, and technological literacy. All of the described skills involve more than just cognitive learning.

For example, the core skills of critical thinking and problem-solving involve substantial elements of human interaction to leverage collective intelligence. Creativity and innovation are also at their best with effective interpersonal interactions. Collaboration and communication are almost by definition rooted in Krathwohl and Bloom’s affective domain.

Creativity and critical thinking are also not solo acts. Dialogue and interpersonal relating tremendously enhance both. It is no accident that innovation clusters or centers tend to be in compact geographies. After all, wasn’t that the idea of a university?

Stuck in the cognitive-only ditch

The time-worn saying of “it’s not what you know but who you know” illustrates a long-held recognition of affective skills. But, if we were to look at the curriculum in any university program, it would be heavily tilted towards a range of cognitive skills and would ignore this idea.

In the business and non-profit management disciplines, where I have taught for decades, quantitative subjects such as finance and accounting reign supreme. Even organizational behavior has been co-opted into an idea of human “resource” management. And, marketing has become a numbers game with customer relationship management (CRM) systems.

In the healthcare disciplines, affective skills are crowded out by all the learning needed for complex medical procedures. But who among us wants a dysfunctional surgical team operating on us?

Even in the liberal arts, learning is often focused on developing “prepositional knowledge” of the discipline's history and seminal theories. The nuances of interpersonal navigation that would seem natural in these disciplines are simply absent.

Flipping the narrative

So, how can we get out of the cognitive ditch? Should we turn to theories such as problem-based learning or challenge learning? It will take much more than a convenient focus on a problem or challenges.

For a start, concepts such as the 4 Cs should be the foundation or the keystones of learning design. Rather than start with the knowledge to be imparted, the focus should shift to developing affective domain abilities and then adding the needed knowledge on an as-needed basis.

The next three installments of this series will bring out ideas and concepts in more detail. Stay tuned for more.

Upcoming topics in the newsletters

Ex4EDU.Report - The next installments of Affective the Affective.

Student360.Report - Is teaching excellence beyond its sell-by date?

EduPartners.news - Learning from the 2U bankruptcy. Would we be better served with OPMs (online program managers) as cooperatives?

About the Ex4EDU.Report, Student360.Report, and EduPartners.news

This report is offered as a free contribution by EduPartner Solutions, an educational services company focused on transformation in higher education. Our services include solutions for developing institutional and program strategies, crafting engaging LearningScapes™, and developing programs for the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Another report we offer is the Student360.Report, which focuses on more granular topics of educational design and delivery. It also is offered as a free-of-charge contribution.

We are also founders of the EduPartners.coop LCA, which supports and sends the newsletter EduPartners.news, which is focused on furthering the use of cooperative and collaborative organizations in higher education.